This is a book that was written by Ilya Grigorik who’s a Web Performance Engineer at Google while also a member of W3C Web Performance working group. His book is called High Performance Browser Networking and overall it’s preeetty good. The book was not all that easy to read, but not all that hard either, it’s moderately long at around 400 pages but can be pretty dry at times… I remember in particular that when we were going through the 60 page long history of Wireless networking I was really starting to question my life’s purpose and the meaning of the universe.

The book goes covers a lot of nice topics and concepts though. Most of them we won’t be able to cover entirely in this post, but they are nonetheless fundamental. It starts off with Networking 101: definition of delay and TCP/UDP performance, goes into TLS, then onto both wired and wireless technologies, and finally HTTP, Websockets, Server Side Events and WebRTC.

Here are some of MY key takeaways.

- Everything should go through a CDN

I have always been able to appreciate the benefits of using for a CDN for static assets such as images/videos, CSS files, JS files, and such. It means that your web servers don’t need to do as much work, and that the assets are globally distributed to be closed to your users.

It turns out that routing ALL your traffic through CDNs can actually be a good idea. The main reason network calls can take a long time for web applications are not so much bandwidth related but latency related. It takes a long time to establish an initial connection to a remote server, it will take at least one full round trip for TCP to establish a connection, and a total of three round trips for a TLS to establish a connection.

Establishing those round trip connections over long distances is costly, the SYN, SYN ACK, ACK, and TLS packets will need to travel a long distance before we can start to send data. But by using a CDN, our users would only need to establish those connections to the closest CDN endpoint which is likely to be much closer than your server. The CDN endpoint will then be able to relay your request and avoid expensive TCP/TLS handshakes by maintaining a pool of long lived open connections.

- Fun fact: last mile latency is where the delays are at

The main highways of the internet which are maintained by ISP vendors and as public infrastructures are highly efficient fiber optic network with huge bandwidth and latency performances. Where the internet slows done is usually at the last mile, in residential areas, where infrastructure is a lot less efficient: wireless networks, copper wires, and outdated routing and load balancing hardware.

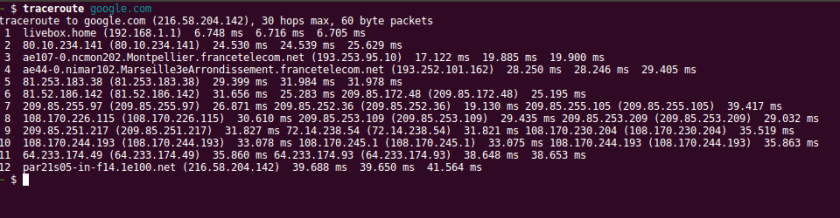

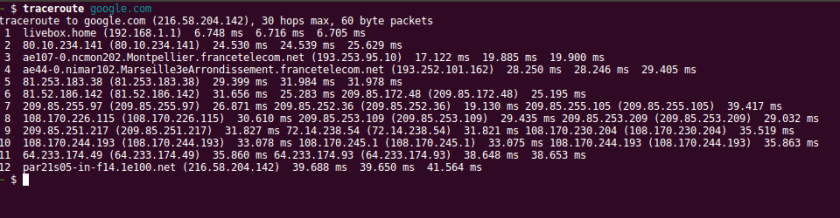

As this traceroute shows, the total it time it takes to reach google is between 39 and 42 ms and there are 12 total hops. But the first hop which connects my computer’s network card to my home’s WiFi router takes a whopping 6 ms, and it then takes another ~ 18 ms to go from my home’s WiFi to what is probably the neighborhood’s router. Over half of the journey is spend going about 100 meters up the street from where I live.

- Mobile networking is screwed

While it would be hard for me to tell you with a straight face that I remembered everything the book covered about mobile networking, my take away is that the radio is the second most battery consuming device on the mobile (only beat by a switched on screen) and that many strategies are used to keep it turned off as much as possible. Although mobile network performance is highly variable as a whole, it’s important to realize that it is still slightly predictable: a lot of time is spend on initial requests actually waiting for the radio to wake up, to listen to the local network tower messages, and to connect to the local network tower.

The ideal mobile networking pattern should look something like this: avoid communications if they are not necessary and if they are then do a lot of communication all at once, preferably in one big request. Avoid polling strategies for instances: having to wake the radio up and send data ever so often is going to end up being costly in terms of battery.

HTTP 2 is an improvement on HTTP 1.x not so much because the API or the interface changes – it doesn’t – but rather because the underlying protocol changes. You would still mainly use HTTP 2 the same way you would use HTTP 1.x, you would just get better performance.

All communications to a host are multiplexed on a single TCP connection, meaning that handshakes don’t have to keep being established for each new request and that some head of line blocking issues can be avoided. The head of line issue that can be avoided is when a HTTP request is being held up because of lost packets, which can prevent further HTTP request of happening is the browser has already opened as many HTTP connections at it will be allowed to (it varies but browser will usually maintain up 6 TCP connections open per host).

Headers are not send of every request. Instead, header tables are maintained by the browser and by the server, and only differences in headers are send on new requests. This means that cookies which can be particularly expensive to send on each request only get sent when their content changes.

Another important feature of HTTP 2 is server push. It enables the server to push additional content to the browser when a resource is requested. User requested /index.html? Send him index.html, but also push other files that he will need, such as index.css, index.js and media files. Why is this nice? Normally browsers would download index.html, find links to additional content, and THEN send a new request for that content. By using server push we are essentially avoiding a whole round trip of latency. Yes, but I was already avoiding this by inline all of my JS and CSS inside my index.html file, why should I do this? By using server push network proxies and the browser are able to more efficiently cache that extra content exactly because it isn’t inlined and arrives as a separate file.

HTTP 2 was based on the SPDY protocol developed at Google.

- Polling, Long Polling (Comet), SSE and Websockets

Many different techniques can be used to achieve more or less the same goal: be notified of updates by the browser as soon as they happen. Implementations and performance differ widely though, and some are better in some situations that others.

Polling is asking for information at a fixed interval. Let’s say that every ten seconds the browser makes a HTTP request to the browser. This is perhaps the most naive and simplest approach, it will however generate a lot of unnecessary server traffic if there is nothing to update, and is royally inefficient for mobiles because having to wake the radio up every ten seconds is slow and expensive for the battery.

Long polling, or comet, is like polling but with a twist. Basically the browser sends a request to which the server will only reply if it has any updates. Sometimes there is no data and the server timeout might kick in after 2 minutes or so, at which point the request will be resent by the browser. This is much better than regular polling as it is not as greedy for the browser or the server. And it is also not that much harder to implement. Some servers might suffer with having a lot of simultaneous open connections, and remember that browsers can only maintain 6 open TCP connections per host and that each long polling request will be using one of those TCP connections.

Server Side Events (SSE) is a rather underused browser API that is however supported by a lot of browsers. The interface is very simple, as the browser simply needs to connect to a REST endpoint, and the server will then have to manage an array of open connections.

var source = new EventSource('/event-source-connections/');

What’s nice about EventSource is that it comes with a few nice to have features such as automatic reconnections performed by the browser when a connection is lost. There are JavaScript polyfills for older browsers that do not supported that internally fall back to Long Polling, if your targeted browser can do xhr requests, it can do EventSource.

WebSockets are not quite the same as the three previous techniques as they allow bidirectional communication between the browser and the server. Their interface is also fairly simple, but events such as disconnections have to be managed by the application. WebSockets also introduce state to the server. If a browser is making a request to a server via a reverse load balancing proxy it’s important that the request end up on the same server every time as WebSockets are connection based: this can be trickier than it sounds. Most WebSockets connections are setup via secure tunnels between the browser and the servers, and some agents over the network may not support WebSockets or behave unexpectedly in their presence. WebSocket polyfills also enable browsers that support xhr to simulate WebSocket behaviour.

There is more good stuff that the book covers. While I still feel that some sections could have been improved or that I felt the absence of any coverage of DNSs, I will still give this book a 5 star rating because the overall content really was in depth, taught me a lot, and has made me a better full stack developer.