I really enjoy the typical CS101 classes like exploring and understanding Operating Systems. Every piece of software ever made runs on an OS at some level. Servers run directly on an OS, desktop apps run on an OS, frontend apps run on browsers that run on an OS, etc.

For someone like me who likes to work on web apps I thought it would be useful to learn some about the inner workings of web browsers. Basically, I had gleaned bits and trinkets of information here and there about how browsers might perform internally, but by and large I didn’t feel like I wasn’t holding the whole picture.

I now feel a lot more confident in my understanding of how browsers work and consider it a very interesting topic even if it’s oft left unexplored. In my quest for understanding it struck me that there isn’t existing document out there. The main ideas I will talk about come from the excellent book length article originally written by Tali Garsiel, and later improved upon by Paul Irish, called How Browsers Work. Most of the readily available information about browser internals mostly revolves around webkit (open source NIX project adopted and use mainly by Apple) and gecko (Mozilla) and so the blog post might be more skewed towards that.

The whole journey has given me more appreciation towards standardised browsers specs and the browser engineering community!

Parsing Files

Browsers have to parse a lot of different files. CSS, HTML, JavaScript, JSON, XML, XHTML, PDF, medias, etc.

It was certainly interesting to learn about how for strict/context-free languages such as XML and CSS browsers are able to use lexer generators such as Flex to tokenize the file, and a parser generator such as Bison to build an AST. There are essentials tools that take in regex and other formal definitions/rules to ultimately build the parse tree you can easily use.

For HTML on the other hand it is not possible to use such tools because HTML is very forgiving. It can have unclosed tags, missing tags, badly named tags and just bad syntax in general, and the browser will do it’s best to understand what is going on and how the best fix the syntax errors. Lexer and Parser generators don’t work well to address these problems, and so what browsers might do is decide to implement a stateful tokenizer, eg. if we are already in an “opened tag” state interpret the following input as X, but if we are in a “between two tags” state parse the following input as Y.

Rendering

DOM

The DOM means Document object model and it is the JavaScript tree representation of all the nodes inside the document. It will contain even node types that are not rendered to the screen such as Node.COMMENT_NODE elements, elements, and elements with display: none or opacity: 0. The DOM is fairly interesting in its own right, it’s a live object and an actual in-JS representation of the freaking document (!) but it’s fairly well understood too.

CSSOM

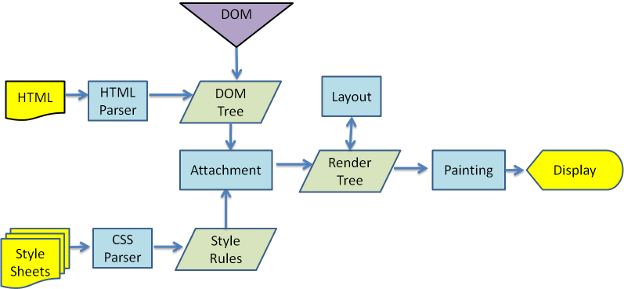

This is where things start to get interesting. The CSSOM would be the “Style Rules” section in the flow chart above. Essentially after the browser parses all the CSS files it will be build one or many Style Context trees that it will use to apply styles to the DOM, to create the Render Tree. Browsers differ on implementations and naming convention a lot here. But what it comes down to is essentially generating one or many CSSOM trees derived from the stylesheets. Often these trees only include native CSS selectors ,

, etc. and do not include CSS selectors such as classes and ids that are more easily written/read to/from hash maps.

Below is an example of what a naive CSSOM might look like.

Render Tree

The render tree is attaching the CSSOM to the DOM. The DOM is traversed and styles are applied to each element. The render tree has a very similar structure to the DOM, but because it is only used for rendering it does not include nodes that do not need to be rendered: , nodes with the display: none rule, etc. It’s at the Render Tree stage that concepts such as deciding which CSS rule is more specific (CSS Specificity) and which rule should be inherited (Cascading) comes into play.

Layout

The step that comes after building the Render Tree is the Layout. This step is tasked with positioning elements on screen. CSS concepts such as Display Modes, the Box Model, and Stacking Contexts come into play in this step.

The browser will start by layout element with the highest stacking context, and start by rendering children within each one of those.

The video below is only 27 seconds long and gives you a pretty good idea of what happens during the layout step. It does also cover the Painting step which we are going to talk about next.

Painting

This is the stage where the layout is filled in with backgrounds, borders, fonts, etc. Just like the layout step, this step can be global (paint the whole Render Tree) or incremental (paint only a changed portion of the Render Tree). This incremental process is enabled by the tree nodes having their dirty flags toggled.

Further Reading

There’s a great deal that could be expanded upon here. Some of these concepts have helped me better understand why the browser might behave the way it does in some circumstances (collapsing margins, stacking contexts).

This area is quite important to understand why browsers operate the way they do and that means that it’s quite important for browser performance. Google Developers has got a good series about the Critical Rendering Path which is all about how to structure the application for a faster first render.